You can contribute to complete this page. Note: This section is under construction. Many tower as high as 30 to 50 feet and are 3 or 4 feet thick.Resources are things that needed to develop a village. If you travelled through Alaska today, you would see totem poles rising in the midst of Indian villages. When finished, this will be the shoulder of a towering “welcome figure,” a type of statue traditionally made by Coast Salish people to welcome visitors to their territories.If your totem pole is to be authentic, see that the figures you carve have some personal meaning to you.

Use the 11 Ostrich figurines to open the chest in the south after using the Clairvoyance spell to get the Gem of Power. All of these - except dino statues - may be provided in the competition chests. These resources are exclusive only on competitions. Those are not stockpiled at warehouses, but instead inventory.

A citizen of the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma and a member of the urban Native community in the Pacific Northwest, Tail has worked on some of these projects as a consultant of yəhaw̓ Indigenous Creatives Collective.“Public art is a chance for people to see themselves reflected in the cityscape, which is so often incredibly colonial: gigantic buildings and steel and metal everywhere — it’s such a constant daily reminder of very painful histories for many people,” Tail says. “Make people realize that we are here as a people, and we’re not going anywhere.”“Grandmother Frog” is part of a growing crop of public artworks by local Indigenous artists that will soon appear across the city and region and send a similar message.In the next months and years, these site-specific artworks — commissioned for Seattle Center’s new Climate Pledge Arena (opening this month), the Washington State Convention Center expansion (2022), the Seattle Waterfront Park (2024), the Seattle Aquarium’s new Ocean Pavilion and elsewhere — will be installed in lobbies, staircases and public plazas to welcome visitors and let them know: You are on Indigenous land.“In a cultural and spiritual sense, having the Indigenous histories of the land — and the current Indigenous presence on the land — recognized in physical formats is hugely meaningful,” says local artist and curator Asia Tail. “She’s there to protect, look over,” Wilbur-Sigo says. The new ?ál?al facility will include affordable housing for Native Americans and a wide-ranging contemporary art collection. (While the ban was short-lived, the exclusion of Native Americans continued in other ways.)Now, more than 150 years later, “Grandmother Frog” will welcome people to this “sacred spot,” says Wilbur-Sigo. They were used as a courtesy not to interrupt a.Not long after, Yesler and other leaders of the newly incorporated city passed an ordinance banning Native Americans from entering the city.

A sign at the terminal excerpts a 2007 letter from the Tulalip Tribes, noting “This is a living site of our ancestors, and it has immeasurable cultural and spiritual value.”At the terminal, art is everywhere you look. These elements — along with a permanent art collection — are meant to honor the continuing tribal presence on the land.In Mukilteo, tribal leaders from the Lummi, Muckleshoot, Suquamish, Snohomish, Skykomish and other tribes signed the 1855 Point Elliott Treaty, ceding much of their land and retaining the right to continue to fish, hunt and gather as they had and have for generations. The cedar-clad building (which serves one of the state’s busiest ferry routes) has a light ecological footprint, with an architectural design that takes cues from a Coast Salish longhouse. It was the result of a yearslong collaboration of 11 local tribes with the Washington State Department of Transportation and LMN Architects. The hope is to go beyond land acknowledgments — which can often feel perfunctory or performative — toward a more intentional and holistic relationship with Native nations and artists in the region.In December, a brand-new $187.3 million ferry terminal opened on the traditional lands of the Snohomish people.

For Guests from the Great River, installed outside the Burke Museum in late 2020, artists Tony A. Carvers Keith Stevenson and Tyson Simmons of the Muckleshoot Tribe are making a welcome figure for the new downtown Auburn Arts Alley (Spring 2022) and will also be collaborating on a public art project for a new recycling and waste transfer station in Algona, WA (2023).While the region will soon be home to several new traditional Coast Salish carvings, such as welcome figures, some artists are bringing newer techniques and materials to their commissions, as well as influences from other tribes. And near the toll plaza stand two welcome figures by Suquamish artist Kate Ahvakana and five embossed aluminum panels by Shoalwater Bay artist Earl Davis.Seattle and King County arts agencies are also working on a variety of large-scale projects involving local Indigenous artists, including Duwamish artist Michael Halady, who is carving a welcome figure from a 600-year-old cedar pole for the main terminal at the King County International Airport/Boeing Field (2022). In the elevator shaft: glass panels by Tulalip master carver James Madison portray orcas, salmon and tribal elders. Near the ticket booth: an 8-foot diameter spindle whorl (also by Gobin) depicts ancestral connections to the waters and sea life of Puget Sound.

STG Presents has tapped Joseph H. This in turn has resulted in more commissions going to women and first-time public artists.Asia Tail traces the changes back to a few things: mainly, the yearslong advocacy work by Native artists and others behind the scenes, as well as “a readiness on the part of mainstream agencies to actually start putting action behind these ideals of DEI — diversity, equity, inclusion — and actually realizing it.”Private institutions and nonprofits are making similar moves. The duo is also creating two large-scale glass and steel canoe paddle sculptures for the city of Seattle’s Ship Canal Water Quality Project (2024).The increase in commissions for Native artists is in part due to institutions hiring Native art consultants and crafting calls for art specifically by Indigenous artists in order to bring more people into the fold.

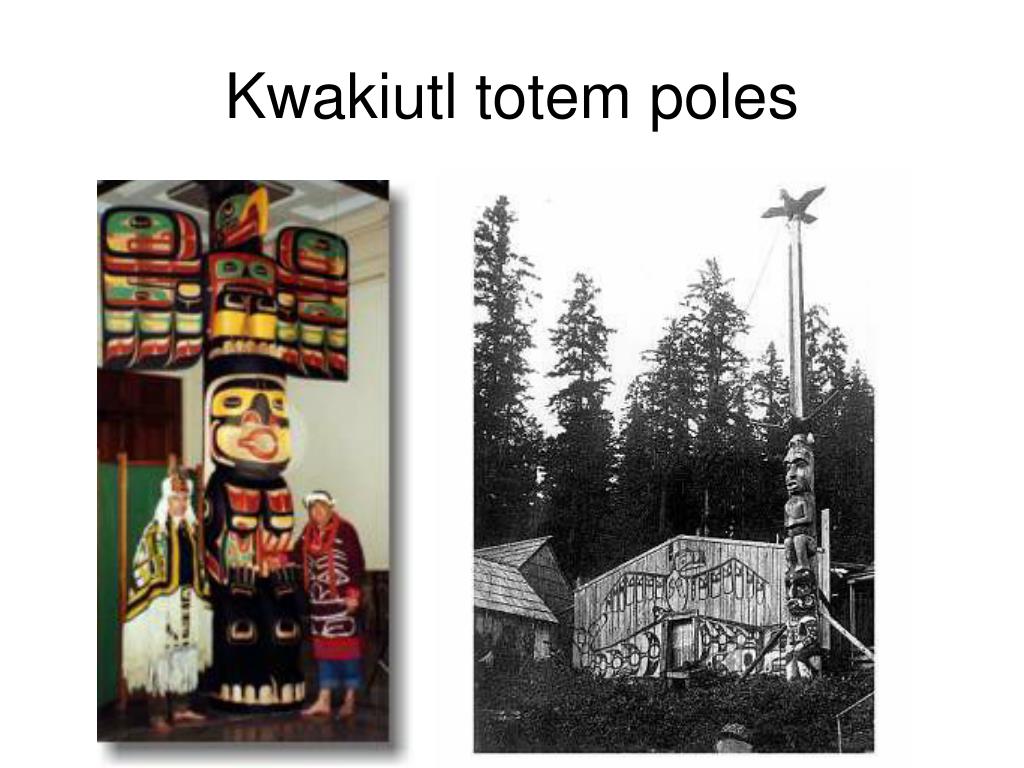

“It’s starting to be understood. “All of a sudden, it’s starting to become acceptable,” she says. “People are getting comfortable and used to seeing Salish work,” which tends to feature more ovals, trigons, crescents, and welcome figures rather than totem poles. (The totem pole, still there, is part of a National Historic Landmark.) Ever since, totem poles — which Coast Salish people didn’t traditionally make — and formline designs featuring U-forms and ovoids became a catchall for a vague “Northwest Native” style.But since the 1970s, prominent artists like Susan Point and Marvin Oliver (plus, in more recent years, Brian Perry, Shaun Peterson and Andrea Wilbur-Sigo, among others) have paved the way for more recognition for Coast Salish artists and representation in public art collections.Now, with the recent surge in Indigenous public art, “there’s something new happening,” says Wilbur-Sigo. The Seattle Symphony recently unveiled a large woven cedar mat by artist DeAnn Sackman, whose Duwamish lineage can be directly traced to Chief Seattle and his daughter, Kikisebloo aka “Princess Angeline.” Featuring black and red mother-of-pearl shell buttons modeled after Coast Salish iconography depicting songs, the mat will be on permanent display at Benaroya Hall.“I’m honored for the opportunity to represent and share the culture of the Duwamish people and my fifth generation great-grandfather — who the city of Seattle is named after,” Sackman says.While Coast Salish artists have been carving, weaving and creating art here for ages, local traditions and techniques have long been less recognized and sought-after in favor of more northern styles from British Columbia and Southeast Alaska.At the turn of the 19th century, local businessmen stole a totem pole from the Tongass Tlingit and erected it as “the Seattle Totem Pole” in Pioneer Square with a plan to market Seattle as a Gold Rush gateway to Alaska.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)